I recently asked a good friend (

- author of ) what she thought of my work, looking from the outside in. We were sitting on the patio of a bistro in Nolita, on a beautiful Thursday evening, eating as a Citibike rider argued with a truck driver who was illegally double parked by the bike docking station.“You want to create meaning in the world”, she told me, matter-of-factly biting into the crispy baked potato we had ordered. I waited for her to continue. “You want to do meaningful things for others, to give something, you know?”.

I looked at her and thought about how many times I’ve felt directionless unless I was doing something meaningful, offering something of value, holding something together. Was that generosity, curiosity, or performance? Maybe a little bit of it all? Maybe meaning is what we create when we’re trying to make sense of our own restlessness.

It’s incredible how a simple, honest conversation with friends can spark a deeper introspection about something you’ve been avoiding from yourself. So, I set out to explore where our deep need for meaning comes from, and perhaps more importantly, what we do with it.

Why the brain wants to make meaning?

Our brain seeks meaning, and makes it when it can’t find any, because that helps with pattern recognition. And the human brain is wired to find patterns. This is so because if something has meaning, then the brain knows why it happened and can either avoid it in the future (if it’s negative) or replicate it (if it’s positive). Meaning making gives us a sense of certainty in a world that doesn’t have meaning. In fact, Yuval Noah Harari has an interesting thought on this:

As far as we can tell from a purely scientific viewpoint, human life has absolutely no meaning. Humans are the outcome of blind evolutionary processes that operate without goal or purpose. Our actions are not part of some divine cosmic plan, and if planet Earth were to blow up tomorrow morning, the universe would probably keep going about its business as usual.

To some, this may feel bleak - but the inherent meaninglessness of life is a very liberating idea for me. When there is no pre-determined or pre-scribed meaning to things, we are left to our own devices: our imaginations and desires to create it.

Meaning-making, then, is not an end result of life; instead it is essence of being - being present, being intentional, being alive.

We are all story-tellers.

Being human, story-telling, and meaning-making.

The world does not come with inherent narrative arcs or moral lessons; it is full of randomness, unpredictability, and ambiguity. Yet as humans, we are wired to seek patterns, explanations, and coherence. This is where storytelling becomes essential. Stories help us stitch together disconnected events into a narrative that feels logical and emotionally satisfying. In doing so, storytelling transforms chaos into coherence and turns experience into understanding. It helps us organize the messiness of life into something that feels manageable and meaningful.

Psychologist Dan McAdams describes this process as forming a “narrative identity”: the internalized and evolving story of the self that integrates our past, present, and future into a coherent whole. According to his research, we don’t just experience our lives; we interpret them, crafting a storyline that helps explain who we are and why we are the way we are. This narrative gives us a sense of stability over time, especially as we encounter change, trauma, or uncertainty.

Story-telling (which needs meaning-making) also connects us to others. It literally connects us through something known as “neural coupling”. Researchers at Princeton found that when a person tells a story and someone listens, their brain patterns become synchronized: a sign of shared attention and understanding. Isn’t that wild?

Whether it's through religion, family roles, career ambition, or social causes, the stories we tell ourselves help us endure suffering, justify sacrifices, and imagine a future worth striving for. We live in a universe that offers no intrinsic meaning, so our stories are the meaning, and the more consciously we construct them, the more purposeful and intentional our lives become.

In my own therapeutic journey, one of the most powerful exercises I did is called the ‘deathbed journal’. I am not saying you need to do this, in fact — it’s best done with a therapist but I’ll tell you about it here so you can see the connection between meaning, purpose, and our lives.

You imagine yourself at the very end of your life: old, reflective, even at peace, perhaps dying. Like you really picture it (this part of the exercise is a visualization). Then you imagine your present-day self sitting beside older-you. You then have a conversation with your older, dying self. You ask questions like: What mattered most to me? What do I regret? What brought me joy? What do you wish I’d done differently? What must I not forget?

And then, you listen. You let that older version of you speak.

It’s intense, and often emotional. But it reveals something essential: beneath the striving and distractions, we all know what really matters. For me, it was a confrontation with my own avoidance: of creativity, of vulnerability, of service, of choosing a path that felt true rather than impressive. That imaginary conversation didn’t give me all the answers, but it sharpened my sense of what I didn’t want to waste time on anymore.

And it planted the seed that meaning isn’t something you wait to find, it’s something you create by how you choose to live, today.

[Reflection Point]

Complete the sentence:

“If I only had one year left, I would…”

“The legacy I want to leave is…”

“I will feel proud of my life if I…”

“I want to be remembered as someone who…”

Meaning-making is not just youth’s privilege.

We’ve culturally relegated meaning-making to the realm of the young. As if it only belongs to gap years, college essays, and hormonal angst. In your twenties and early thirties, meaning-making feels like a quest: Who am I? What do I want? What kind of life do I want to build?

So, when people in midlife or later ask, What’s next?, What do I care about now?, or What if the old story doesn’t fit anymore?, they’re met with silence or shame. As if asking those questions later in life means you failed earlier. But I think the opposite is true: to keep searching, to stay curious about meaning at every stage of life, is a kind of freedom. The meaning of life and purpose isn’t in the answer. The meaning of life and purpose is in the asking.

The truth is, however, that many people enter midlife feeling betrayed by the answers they were sold. You got the job, the partner, the apartment, and yet a quiet discontent lingers. This is what I call the “the season of marginal dissatisfaction”: a recurring sense that something’s off, even when everything looks fine. Because the truth is, we were told that meaning is something you find early, then live out. We believe the stories we’ve been told that this is the end and there is nothing left to be done.

Midlife is often thought of as arrival; when we should “have it figured out.” But the pressure to solidify meaning early can actually backfire. When meaning is treated as a fixed goal instead of a living process, people in their thirties, forties, and fifties often feel trapped by the very stories they once found comforting.

That’s why I’m really excited to see that media is exploring the nuances of meaning-making and finding purpose later in life through shows like Four Seasons, Grace and Frankie, and books like All Fours, The Midnight Library, and The Perfume Collector.

Some of my favourite films about this:

The Worst Person in the World : A modern bildungsroman about ambiguity, relationships, and the messy middle.

Everything Everywhere All At Once: An existential action comedy about infinite lives, intergenerational trauma, and meaning in the mundane.

The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou: This is perhaps the quintessential absurdist exploration of grief, legacy, and purposelessness.

Becoming comfortable with meaninglessness.

What if none of this means anything?

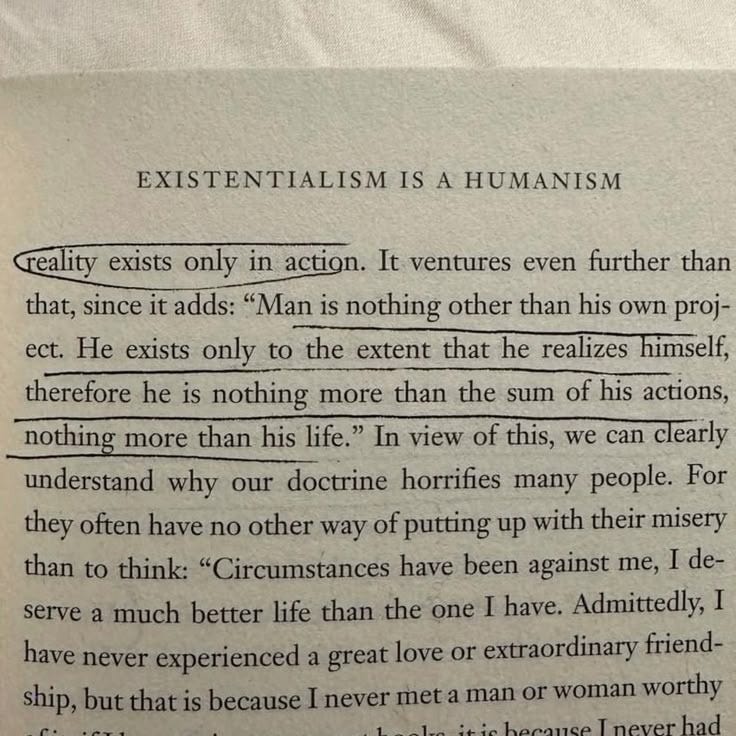

Existentialists didn’t look away from that question, they stared directly at it. Thinkers like Camus, Kierkegaard, and Sartre didn’t pretend meaning was inherent. Instead, they argued that life has no universal meaning and that doesn’t make it empty. It makes it ours.

The discomfort you feel around meaninglessness isn’t failure. It’s friction. It means you’re awake to the reality that control is an illusion, certainty is rare, and no one can tell you how your life should unfold. Once you stop outsourcing meaning to systems, titles, or milestones, you get to ask: What matters to me, truly?

Being comfortable with meaninglessness doesn’t mean becoming apathetic. It means building a deeper tolerance for life’s lack of guarantees, embracing both certain and uncertain moments, rooting in presence, and showing up with curiosity, love, and integrity.

[Reflection Point]

The “What If It Doesn’t Mean Anything?” journal prompt

Write down the question: What if this doesn’t mean anything? in the context of your current struggle (a job, a breakup, a health issue, etc.).

Then write for 10 minutes without editing, correcting, or stopping yourself. Explore:

What would change if this situation didn’t have a larger purpose?

What freedom would that give you?

Can meaning still come from how you respond to it?

Absurd Affirmation (inspired by Camus)

Choose one ordinary thing to do with absurd devotion. Water your plants like it’s a spiritual ritual. Make your bed with operatic flair. Pour your morning coffee like you’re painting the Mona Lisa. It’s a quiet rebellion against the idea that only “important” things matter.

“What Still Matters?” meditation

Sit in silence and ask yourself: If nothing had to matter, what still would?

This helps you strip away the performative, inherited, or external meanings and get closer to your personal values.

Carl Jung believed that the search for meaning was central to human life, a necessity of the soul. He called this the process of individuation: the unfolding of your true self over time. Meaning, in Jung’s view, doesn’t come from conforming to societal roles, but from aligning with your deeper inner life.

And I wholeheartedly agree with him. My friend from the story at the beginning is right: I do want to create meaning in a world that is largely meaningless. I believe that we don’t find meaning, and then after that, live our lives. Meaning making is the work of being alive. And if we’re lucky, we get to keep making meaning. Not just once, but again and again, as we evolve, reflect, and become more fully ourselves.

That’s all for now! May your tables, health, and happiness be always in abundance. Live well + be well xx,

Israa

[Ps. My book, Toxic Productivity, is available everywhere books are sold. You can learn more about it here: https://www.israanasir.com/toxic-productivity ].

This has helped shade light on a few things . Definitely sharing this with my friends !

Really enjoyed this one, Israa! Definitely plan on sharing it with someone about to embark on a life milestone.